Letting Go of the Process

January 19, 2026

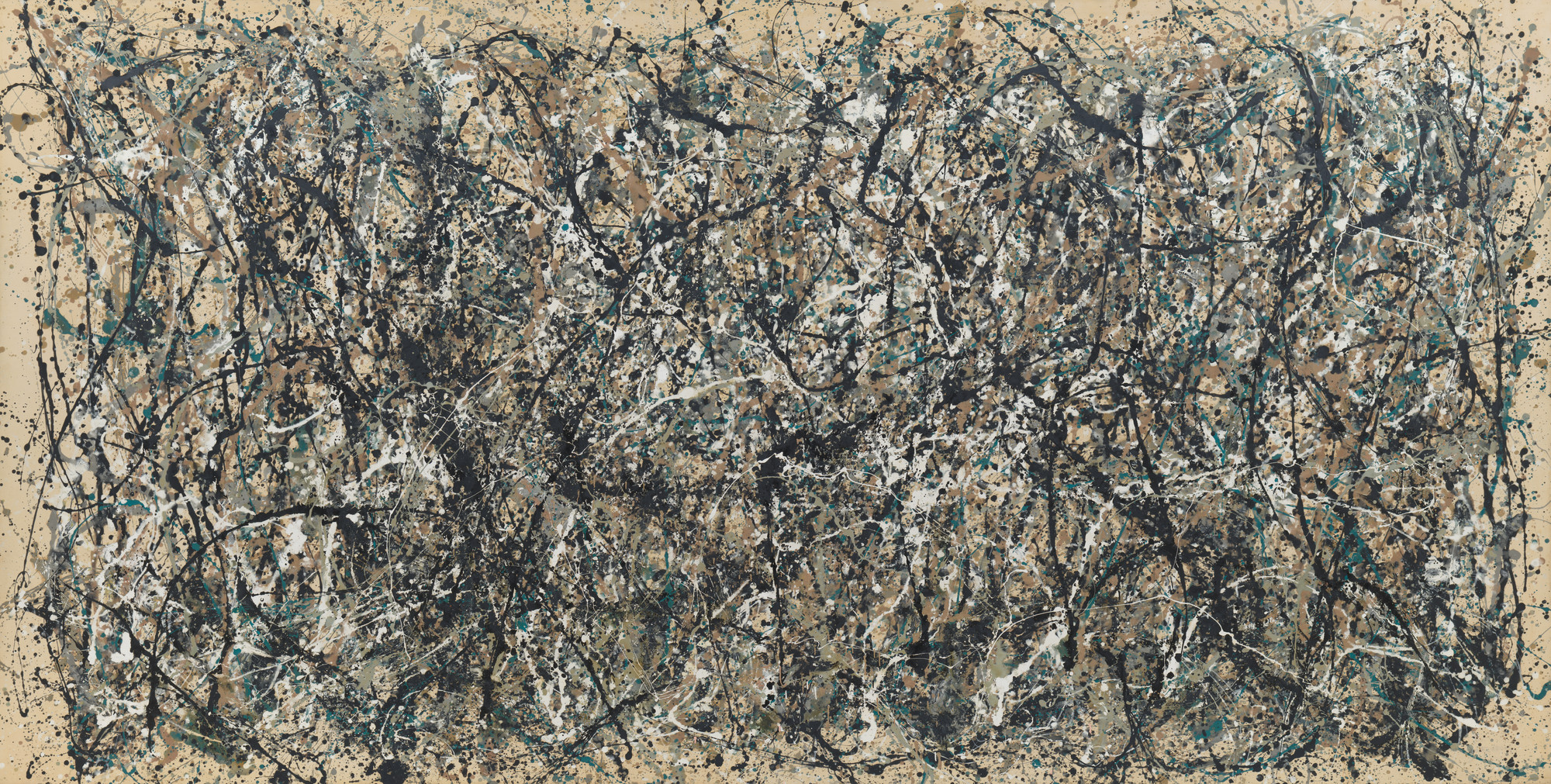

Jackson Pollock, One: Number 31, 1950.

Jackson Pollock, One: Number 31, 1950.

About a month ago, a video called "Why Designers Can No Longer Trust the Design Process” went viral in my small designer circle. If you haven't watched it, I highly recommend watching it first if possible: here is the Youtube link.

The speaker, Jenny Wen, is a designer who is and has been working on great products such as Claude & Figma.

Her main idea is simple: ditch the traditional "double-diamond" process — she didn't really believe it before, and there are even more reasons to ditch it in the current AI era:

- From a result's perspective, the double-diamond doesn't guarantee a good product, and most great products (she's seen) don't follow that process necessarily

- From a time & resource perspective, it spends too much time on the artifacts of the process instead of the final product. For example, we might spend too much time on generating personas, user journey maps, and that kind of jazz.

- From a context perspective, every product and every team is different, so we can't expect to follow the same process in every scenario.

Couldn't Agree More

My initial reaction was: wow, finally, some one said it out loud. This really resonates with what I've been experiencing as a product/UX designer. For the humble 3 years of my designer career, I've worked on various products, each of them have different conditions and team vibes. But there is one thing in common: time is always limited, and the deadline is always yesterday. So we skipped steps all the time. We used our intuitions (or a fancier name called "heuristics") because that's the fastest way to do it. And things seem to be going well NOT following the perfect double diamond process.

Prototyping is Cheap Now with AI

Besides my personal experience, AI, specifically vibe coding, also changed my perspective on the process. I once believed in the "brainstorm → low fidelity → high fidelity" process because back then, software development was much more expensive than a couple of prototypes in Figma. But now things are totally different. AI can generate fully workable prototypes in minutes, so why do we still need those in-between steps?

The Caveat

However, (this might just be my selfish self not willing to ditch my past education entirely), I don't think the double-diamond is completely useless. I still find the mindset of the iteration, convergence, and divergence valuable, and the research phase is always nice to have (if we have time!) to know more about the unknowns. What we shouldn't do is to blindly "worship" that golden process for all scenarios.

The Shattering

Before that video came out, as much as I know that the double diamond process might not be working, I still felt hesitant. The idea of having a solid process gives me a sense of safety — having something to lean back to. However, as cliché as it is, the only constant in this world is change. And as designers, we just happened to work in this tech circle where changes are much more rapid than the rest of the world.

What Does It Mean to Be a Designer?

Now the old tradition is shattering, and the new paradigm has not been formed yet. That makes me wonder, what does it really mean to be a designer?

Going back to Jenny's video, she mentioned some ways good designs are made: start from the solution (how radical!), caring about the details, intuition, skipping steps, and doing something just for the sake of making people smile.

Solution Oriented

Of all these points, there's one that particularly challenges conventional wisdom: starting from the solution. This reminds me of another piece of writing of mine about creative problem solving.

For "Problem-oriented" products, as I was taught in my design education, we focus on the problem, and all the solutions are a reaction to that problem.

And for "Solution-oriented" products — first of all, maybe we shouldn't use the word solution because it indicates there is a problem, and there might not be one — we focus on the things that we create that might make people smile, as Jenny put it.

To be honest, I think both of those methods are good, but just for different kinds of scenarios. I might personally favor "Solution-oriented" because this is how my brain works — it just can't help thinking about the solution even at the very beginning!

Circling Back

Before drifting too far from the question of the designer's meaning and value, I want to circle back on my own answer. First of all, I agreed with all those points: intuition, craft, and being flexible in the process.

For me, it all comes down to one word: empathy.

As designers, we are able to think in others' shoes. We are able to imagine what's it like in other's situations. That's a big part of our intuition. And because we care so much, we obsess over the details and the craft. We're more than willing to question the process and be flexible because we care about the people and the product more than the doctrines.

And maybe that's the whole point—good design has always been about people, not processes.