All AI and No Thinking Makes Jack a Dull Boy

January 12, 2026

When Claude Sonnet 4 first came around half a year ago, I was amazed by its writing abilities. It was just like a wise old man. I could throw a crappy draft at it, and it would throw back a perfect final article. Every sentence was impeccable and even a bit punchy. I could never write as well as Claude.

But some time later, I noticed something wasn’t right. When I looked back at my articles, they felt so strange to me. I didn’t think they were mine anymore — of course they weren’t, Claude wrote them, not me!

And what scared me most was that I felt like I was gradually losing my ability to write. I needed to check every bit of my writing with AI. And it became more and more uncomfortable for me to come up with a full sentence by myself.

This wasn’t just my personal experience. Back in 2023, there were already studies revealing the impact of LLM tools on human brain functions:

…early dependence on LLM tools appeared to have impaired long-term semantic retention and contextual memory, limiting their ability to reconstruct content without assistance. - Fermat’s Library, Your Brain on ChatGPT, 2023

The Atrophy of Writing Muscles

This atrophy of brain functions reminds me of my workouts.

To me, writing is very much like jogging. It takes some effort to kick-start, there might be some discomfort along the way, but it feels really, really good after the workout. It refreshes me entirely, and my muscle grows so that I can do better next time.

Outsourcing most of the writing to AI is just like growing lazy for the brain. After a while, we will gradually lose that part of the muscle, and we will suffer greater pain to regain it.

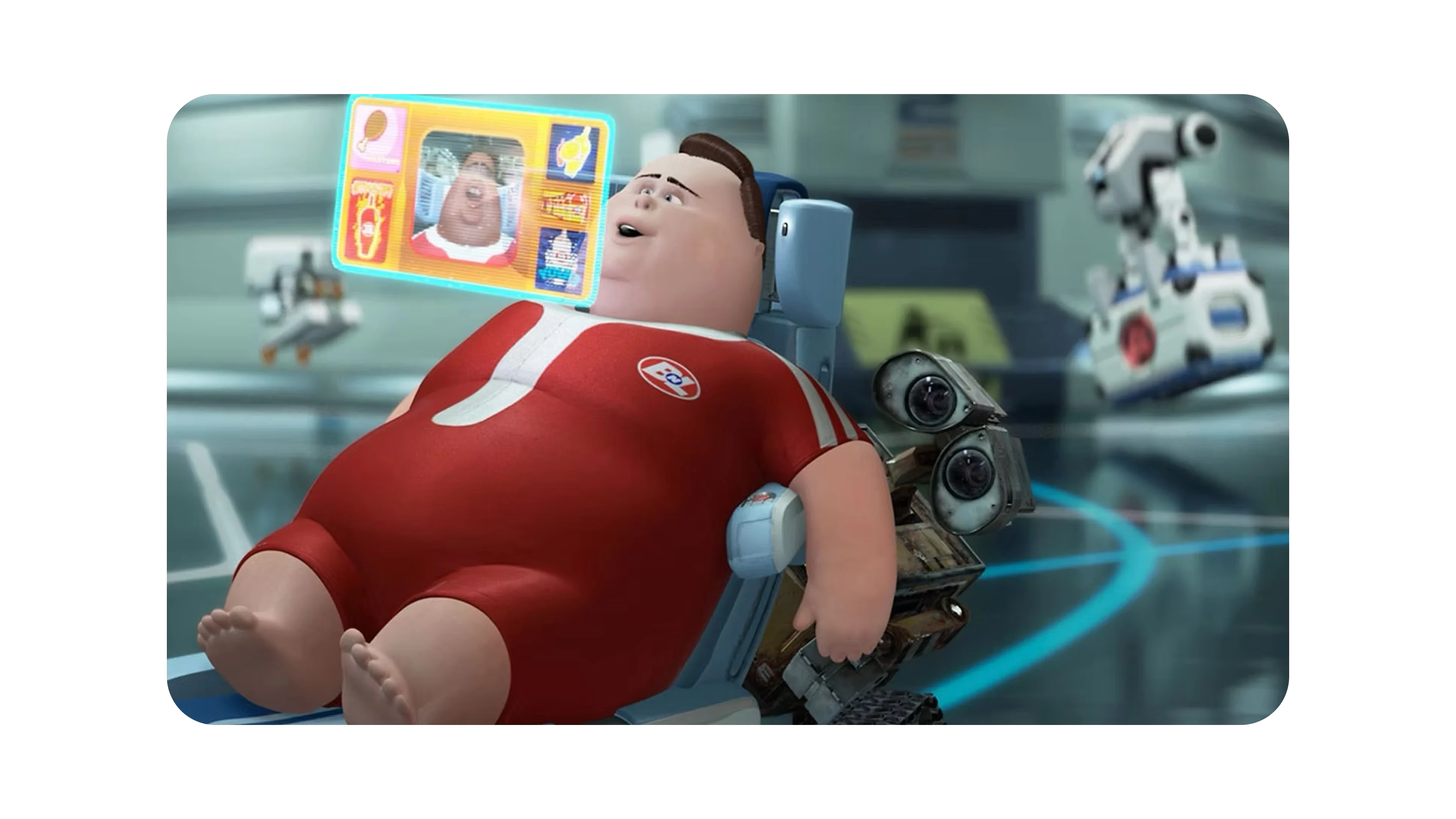

[fig 1] It reminds me of the people in the movie WALL-E: they are so lazy to even walk so that they just sit on a rolling chair all day.

[fig 1] It reminds me of the people in the movie WALL-E: they are so lazy to even walk so that they just sit on a rolling chair all day.

It's Not Just Writing

This atrophy isn’t just about writing abilities, it’s also seeping into how we read and just how we think in general. After all, both writing and reading are just a part of our ability to think — we read to internalize what we think, and we write to externalize how we think.

More often than not, I find myself very impatient while being confronted with a wall of text. I have this urge again to ask Claude to give me a TL; DR. And all the social media platforms caught this trend, and now all the contents became shorter and more eye-catching.

Ultimately, we just want to have a quick grab of the content, and we don’t care about the structure or the narrative. We just want a bullet point summary. We don’t care whether it’s written as a sonnet or a research paper. Those TL; DRs are just like fast food — they provide nutrients, but we are losing the ability to taste slow food, such as a contemplative poem or a complex reasoning article.

Brain First, Then LLM

The question then becomes: can we use AI without losing ourselves?

The result from that Fermat’s Library paper I quoted earlier had another group: the brain-first-then-LLM group, which performs the best in all groups. This group wrote the essay by themselves first, and then sought the help of LLM tools.

What this means is that, instead of going to LLM immediately, we have to use our brains first. AI should be a handy tool that builds on what we think, rather than replacing it.

All AI and no thinking makes Jack a dull boy.

Thinking first keeps us sharp.